British Connection

A Brief History Of

Kussowlie Or Kasauli

As We Call It

Britishers bought the Kasauli land for Rs 5000 to build a military station. But they left behind a popular hill station and a truly beautiful heritage…

This Is How Kasauli Looked Like More Than 150 Years Ago | Video

Kasauli’s British history begins with the end of the Gorkha war. Fought over the domination of the hills, the Anglo-Nepalese war broke out on November 1, 1814 and by the winters of 1815, Gorkhas had lost their territories to the British in the present-day Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand states.

The Treaty of Sagauli, officially declaring the end of the war and making Britishers the new masters of the hills, was signed between the Gorkhas and the Britishers on March 4, 1816.

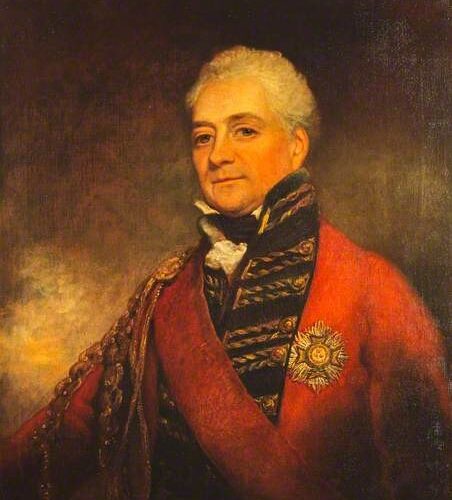

David Ochterlony, a political agent of the East India Company posted in Ludhiana at that time and the hero of the Anglo-Gorkha war, decided to retain control of the Sabathu fort, a strategically vital asset the Gorkhas had lost.

Ochterlony, who in his career rose to the position of Major General and held the powerful post of British Resident to the Mughal court in Delhi, also held on to the Malaun fort, which lies in the Solan district of Himachal Pradesh and borders Bilaspur district and the Nalagarh area.

At these forts, the strength of troops was kept at minimum.

According to the Records of the Ludhiana Agency (1911), it was decided that the “garrisons of these forts to have irregular troops and no larger proportion of regular troops may be stationed.”

Britishers had now the entire control of the hills and restored most hill states to their original rulers and formed the Simla Hill States — a collection of 20 princely states. These states had been invaded and overran by the Gorkhas in the early parts of the 19th century. And to run these princely states, Ochterlony was given two assistants in 2015: Captain G Birch at Nahan and Lieutenant R Ross at Sabathu.

Some princely states like Baghat (which owned Kasauli land) and Keonthal (from which most of the Shimla was later carved out), which had not helped Britishers in the war against Gorkhas, had to face the consequences. Parts of these states were sold for being “unfriendly.”

According to the Gazetteer of the Simla District (1888-89), “Baghat, moreover, had shown himself unfriendly towards us, while Keonthal refused to bear any portion of the expenses of the war.”

Parts of these two princely states were retained by Britishers and the rest sold to a rather friendly Patiala state for Rs 2,80,000.

Sabathu becomes the British headquarters

In the years after the end of the Gorkha war, Sabathu became the seat of administration as Britishers took control of the hill states. Political agents were appointed and posted in Sabathu to run the affairs of the hill states.

It was around this time that many British officers of the East India Company had started exploring the hills surrounding Sabathu and up to and beyond Shimla. While Shimla saw the first British settlement as early as 1819 when the first cottage was built there by Lieutenant R Ross, who was stationed in Sabathu as Assistant Agent of the Governor General, it was not until the early 1840s that Kasauli saw its first foreign inhabitants.

Colonel H T Tapp’s Kasauli survey

As a possible war with Punjab loomed following the death of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the East India Company had started looking for strategic locations in the hills to keep its troops.

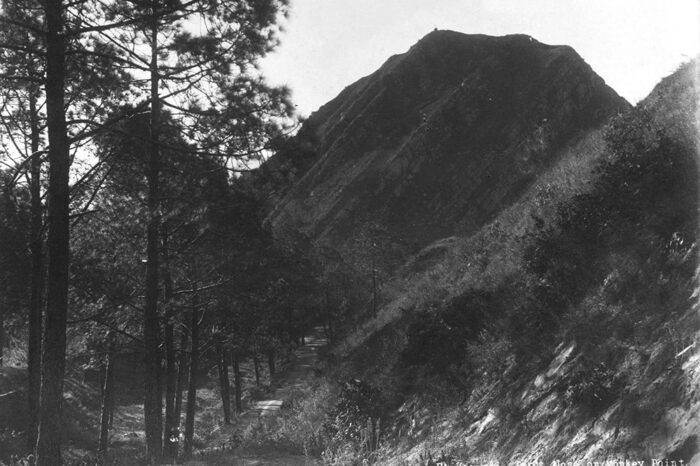

To check the possibility of a military station, Colonel H T Tapp, who was posted in Sabathu and served as a political agent to the Simla hill states from 1836 to 1841, carried out the first survey of Kasauli. The survey by Tapp was one of the first definite steps towards building a military station in Kasauli and for many years the highest point of Kasauli (Monkey Point) used to be called ‘Tapp’s nose.’

May be the shape of the highest hill point did look like Tapp’s nose.

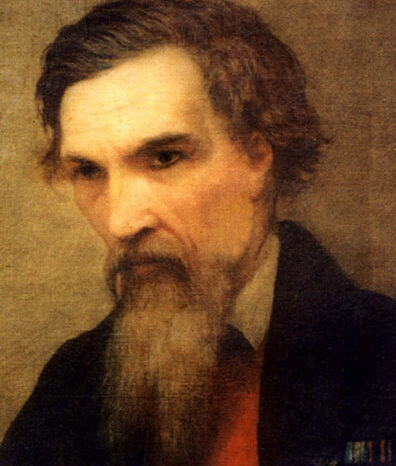

Henry Lawrence: The first European resident

The first British man, who started living in Kasauli, was Henry Lawrence. A British army officer, Lawrence had later founded the Lawrence school in Sanawar for the children of British soldiers.

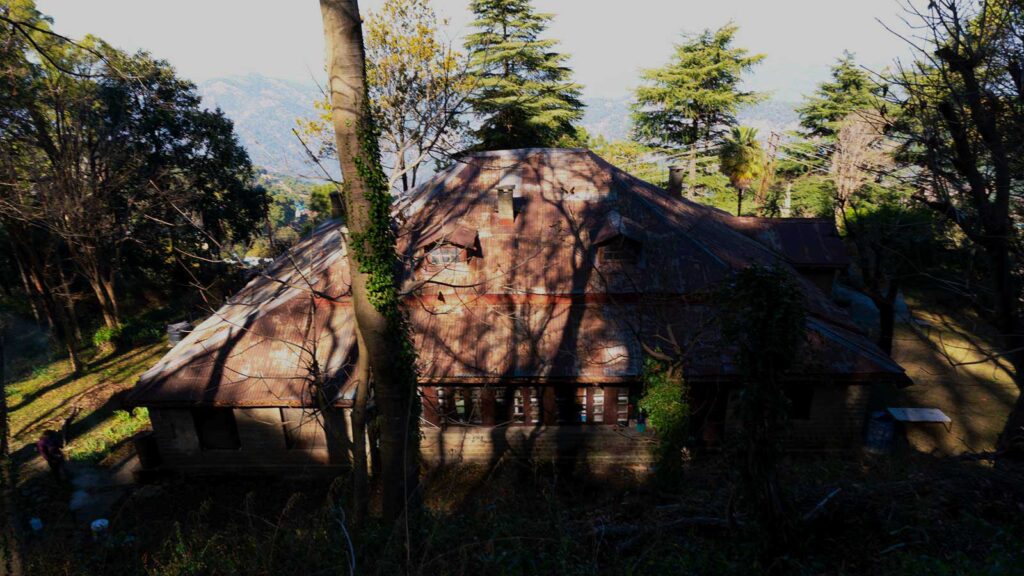

Lawrence served at difference places including in Punjab and also lived in Sabathu. According to various accounts, after his newborn daughter, Letitia Catherine Lawrence (November 16, 1840-August 1, 1841), died of Malaria in Subathu, Lawrence shifted and built a cottage in Kasauli he named ‘Sunnyside’ in 1841.

Letitia was buried in Sabathu. The little child’s death must have been heart-breaking. A letter written by Henry’s wife Honoria Lawrence, when the family was living in Kasauli in the Sunnyside, overlooking Sabathu, reads: “From our house, we can see the burial ground at Subathoo where the mortal remains of our little angel lie. It is on a solitary hill above Subathoo, ten miles from Kussowlie.” The Sunnyside cottage exists even today.

The land for Kasauli is bought for Rs 5000

Kasauli was founded in 1842 as a military station as the nearby Dagshai and Jatogh were in the later years. The idea was to keep troops at strategic locations, which could also serve as sanitariums for convalescing British soldiers. Also, in the early 1840s the Britishers were looking at a possible war with Punjab following the death of Maharaja Ranjit Singh in 1839 and needed military stations for keeping troops,

The cantonments served as valuable strategic basis. It was possible to rush down troops to the plains at short notice from these posts. According to the Gazetteer of the Simla District (1888-89), “It would be necessary for us to retain such portion of the country as appeared best adapted for favorable military positions.”

According to Pamela Kanwar, writer and historian, “These military posts provided a ready-made ring of protective cantonments around the future summer capital of India (Shimla).”

The land on which Kasauli exists today originally belonged to the Baghat princely state, which ruled in parts of the present-day Solan district of Himachal Pradesh.

Following the defeat of Gorkhas, Britishers as a punishment for non-cooperation in the war had sold the three fourths of the Baghat state to Patiala state for Rs 1,30,000 and restored the rest to Rana Mahinder Singh, the ruler at that time. Mahinder Singh died without heir on July 11, 1839 and the state was treated as a lapse.

The state was restored to Bije Singh, the brother of Mahinder Singh in 1842 and in the same year for a sum of Rs 5000 and an annual payment of Rs 507, the Kasauli land was taken over from the Baghat state. The annual payment was discontinued sometimes later.

More land was added in 1844 by acquiring nearby villages of Chattian and Nari on the Kasauli hill from the state of Bija. A sum of Rs 100 was paid as compensation and later the sum was reduced to Rs 80.

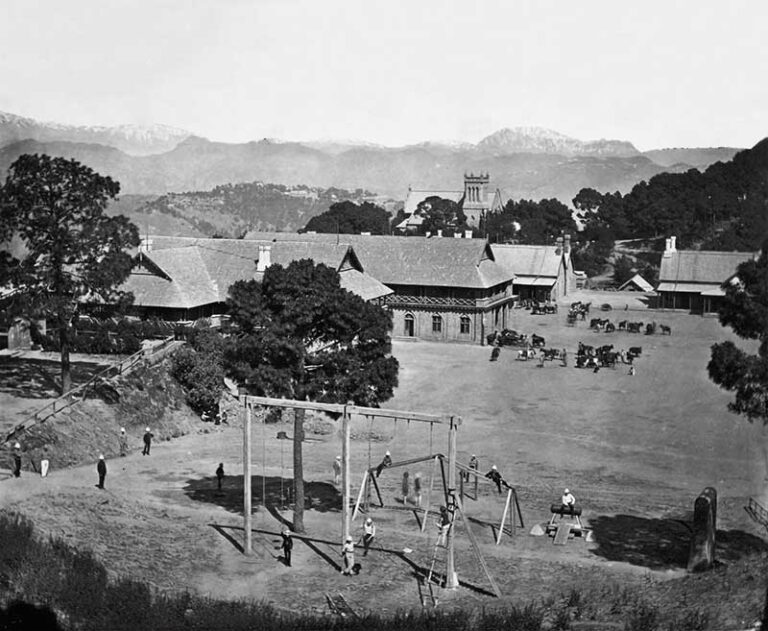

The making of Kasauli

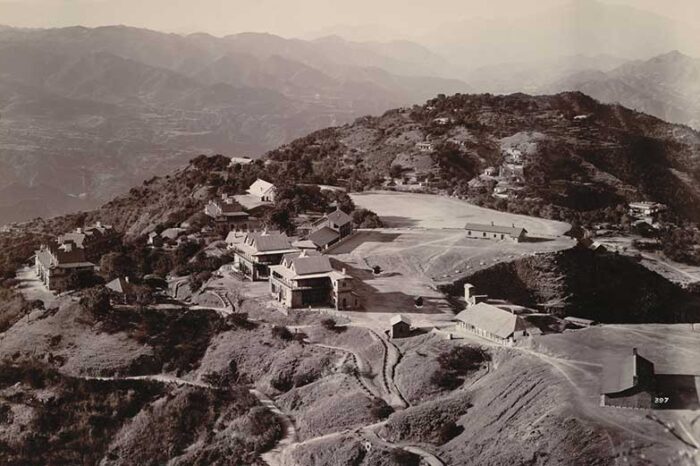

One of the first structures that came up in Kasauli hills after the land was acquired included the military barracks, the Christ Church and the nearby Lawrence school in Sanawar. By 1843, first British troops, the 13th Infantry, had arrived in Kasauli straight from Kabul.

According to Gazetteer of the Simla District (1888-89), Kasauli’s “two barracks contained accommodation for 500-600 troops and during eight months of the year remain fully occupied by convalescents.”

Walter Raleigh Gilbert, an army officer, who had fought in the Anglo-Sikh wars, also got himself built a house in Kasauli. The Gilbert trail is named after him and the house he got built is today known as the ‘Gilbert House’ and is the official residence of the station commander.

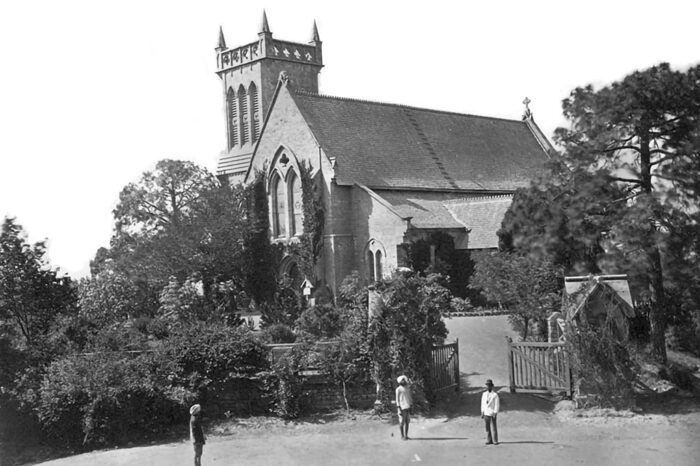

Christ Church

Two years later, the Christ Church, an Anglican church was founded in 1844 for the British soldiers and their families. These were the initial years of Kasauli’s coming into being. It was also the same year when Daniel Wilson, the Bishop of Calcutta (Kolkata) at that time, had visited Shimla and laid the foundation of the Christ Church there.

Kasauli’s Christ Church was opened for service in 1853 and it was consecrated in 1857. In the later years, the church tower was raised and a clock was placed.

Lawrence Military Asylum

Three years later in 1847, Henry Lawrence started the work on the Lawrence Military Asylum in the nearby Sanawar under the supervision of his friend Major W Hodson of ‘Hodson’s Horse’ fame. This land, measuring about 100 acres, also belonged to the Bhagat state.

The asylum was started for taking care and educating the orphans of British soldiers, who had died while serving in India. Its first published rule stated that the objective of the institution is “to provide for the orphan and other children of soldiers serving or having served in India an asylum from the debilitating effects of a tropical climate and the demoralizing influence of barrack life…”

The asylum’s particular location in Sanawar was selected owing to its closeness to the cantonments of Kasauli, Sabathu and Dagshai and if needed protection could have been easily sought immediately.

In The Life of Hodson of Hodson’s Horse, Captain Lionel J Trotter writes, “As early as August 1846, Hodson and two engineer officers had set out with Lawrence in search of a fitting site for the asylum which Lawrence had long been eager to erect among the Himalayan pines and cedars for the benefit of the children of our European soldiers.”

It seems that Lawrence had first chosen a site in Kasauli but later selected Sanawar as he says in a letter, “We nearly fixed on a spur of the Kussowlie Hill, but eventually selected the hill of Sanawar as combining most of the requisites for an asylum viz., isolation, with ample space and plenty of water, at a good height, in a healthy locality not far from European troops. The selection was most fortunate, and I doubt not I owe it to my companions.”

Lawrence had contributed Rs 87,000 for building the asylum. The school was formally opened on 15 April, 1847 with seven boys, seven girls, one master and one mistress-in-charge. By 1853 the strength had grown to 195 pupils.

In 1852, the land occupied by Lawrence Military Asylum, was taken over by the British government from the state of Baghat, which from 1849 to 1861 was considered as a lapse in the absence of heirs. The government took complete control of the asylum in 1858 following the Indian mutiny of 1857. In 1883, the school had 235 boys and 186 girls as students.

Edward Dyer sets up Kasauli Brewery

For Britishers living here, what lacked at that time was a brewery that could produce quality beer at relatively cheaper rates. As late as 1870s, English beer was still costing between Rs 7 and Rs 10 a bottle. In came, Edward Dyer. He was the father of Reginald Edward Dyer. Yes, the same Reginald Edward Dyer, also known as the Butcher of Amritsar for his Jallianawala Bagh massacre orders.

Edward senior set up his brewery in Garkhal, Kasauli in 1855. But he was not the first one to start a brewery in Kasauli. According to many historic documents, the first brewery was set up in the 1840s in Kasauli but was shut sometimes later. It’s not clear who had started it (at least we couldn’t find anything).

Edward had set up the brewery in Kasauli mainly due to the abundance of spring water and of course the cool climate was most suitable. His business boomed and Edward went on to set up breweries in other parts including Shimla and Lucknow. The brewery was later shifted to Solan.

Edward sold his breweries to rival HG Meakin in 1887. After independence, Narendra Nath Mohan bought Dyer Meakin breweries and took over the management. Kasauli brewery, now a distillery, still exists today and is operational.

Mutiny in Kasauli by Gorkha soldiers

A rather peaceful Kasauli of those days was also not left untouched by the great Indian mutiny of 1857. At that time, there were two British regiments — 1st and 2nd Fusiliers — and a Gorkha regiment, also known as the Nasiri battalion, stationed in Kasauli.

The Nasiri battalion consisted of Gorkha soldiers and had been formed after the Anglo-Gorkha war of 1814-16. All troops were ordered to march to Ambala as they were needed in the plains to suppress the mutiny. While the British regiments followed the orders, the Gorkha regiment revolted and refused to move, sending a panic wave among British residents in Kasauli and Shimla.

The Gorkha soldiers, some 80 in numbers, looted Rs 7000 from the treasury and marched off to Jatogh cantonment near Shimla to join their comrades. At Jutogh also, the Gorkha soldiers had rebelled and came out of their barracks shouting slogans against their officers. As news of Gorkha rebellion spread, fearful and panic-stricken British inhabitants fled Shimla and took shelter in the nearby princely states especially in the Keonthal state.

William Hay, the Deputy Commissioner of Shimla, and Major Bagot, commanding officer, spoke to the soldiers and succeeded in persuading them to return to their barracks. No blood was shed and the Gorkha soldiers from Kasauli also laid down their weapons and surrendered the looted money.

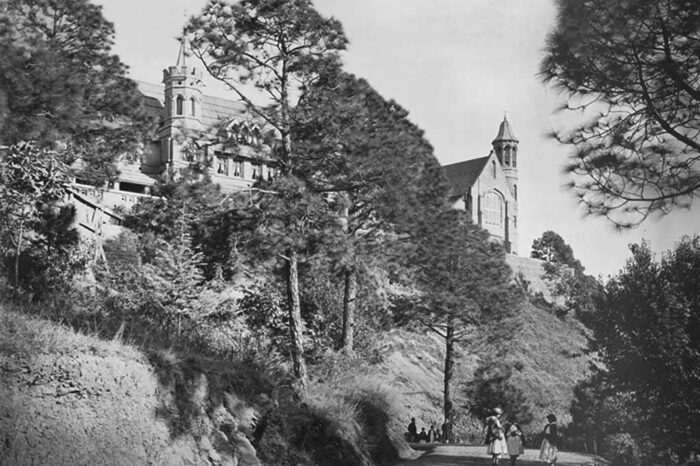

Kasauli expands

By the 1860s, Kasauli had become a popular town. Connected with Shimla through a cart road, Kasauli was also the first stage on the old bridle road from Kalka to Shimla via Sabathu.

According to the Gazetteer of the Simla District (1888-89), Kasauli’s population had reached 3010 by 1868. Houses, hotels, a bazaar, dispensary and a school had come up as the Gazetteer states: “There are about fifty houses occupied by visitors from the plains, and several hotels, also churches belonging to the Anglican, Roman Catholic and Presbyterian bodies. It has a fairly supplied bazaar containing police station, dispensary and a school.”

A club for the elite

Kasauli had become a popular destination after Shimla and it was now time for a club where the elites of the town could socialize. Thus came the establishment of ‘Kasauli Reading and Assembly Rooms’ in 1880. It became Kasauli Club in 1898 after it was registered in Lahore and the management was shifted into the hands of army officers and civil servants.

There was an attempt to sell the club in 1947 by members headed by Sir Maurice Gwyer. However, Colonel ML Ahuja, the first Indian chairman of the club, stopped it from happening.

Pasteur institute established

Another historic moment of Kasauli came when Pasteur Institute was established by David Semple in 1900. Such an institute was one of the first ones in the world set up for developing a cure for rabies. Five years later, the Central Research Institute was founded and Semple became the director institute and held that post until 1913.

In 1939, the Pasteur Institute, Central Research Institute and the Drumbar estate were merged. Semple, a British army officer, had in 1911 developed here an anti-rabies vaccine, which, was widely accepted and most commonly used vaccine throughout the world till 2000. However, its use is no longer advocated by the World Health Organisation (WHO).

The institute has also developed a host of other life-saving vaccines and serum including for the treatment of snake bite cases.

Britishers Leave Kasauli

By the latter part of the 1940s, most settlers had left Kasauli after selling off their properties to the wealthy Indians.

References

Records of the Ludhiana Agency (1911)

Kasauli — A Study in Contrasts (1929) by Major S Smith

A list of Inscriptions on Christian Tombs or Monuments in the Punjab, North West Frontier Province, Kashmir and Afghanistan. (1910)

The Life of Hodson of Hodson’s Horse by Captain Lionel J Trotter (1901)

Punjab Mutiny Records (1911)

Life of Sir Henry Lawrence by H B Edwardes and Herman Merivale (1872)

Gazetteer of the Simla District (1888-89)

The Urban History of Shimla by Pamela Kanwar (1982)