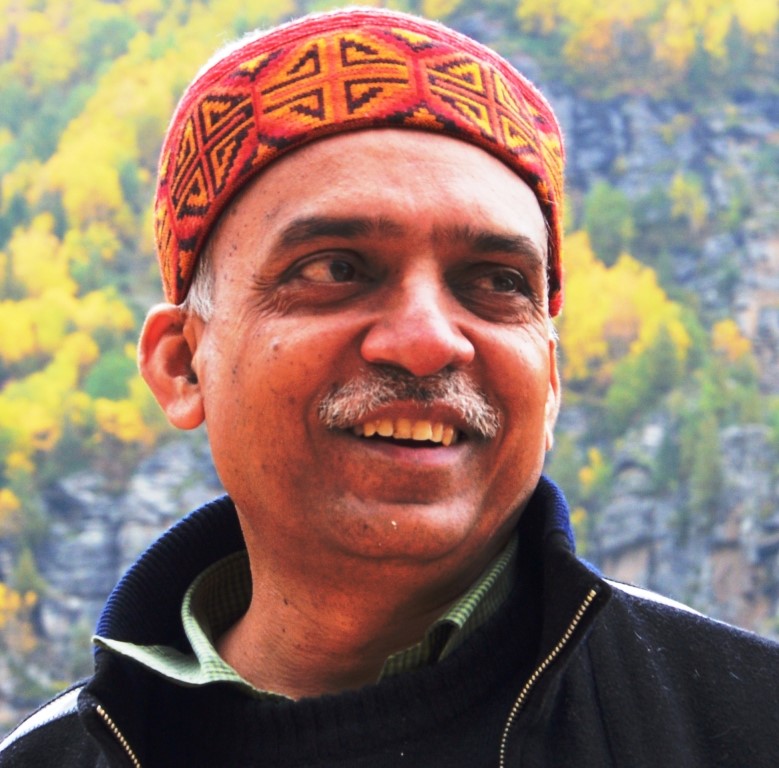

Profile

ONLY ROADLESSNESS CAN PROTECT THE GREAT HIMALAYAN NATIONAL PARK

Sanjeeva Pandey, a former Indian Forest Service (IFS) officer, knows the Great Himalayan National Park (GHNP) like the back of his hand. For over nine years, Mr Pandey, while serving as the GHNP Director, traversed the length and breadth of the Park knowing and understanding a little more everyday about its rich and precious biodiversity spread over 1171 sq km in Kullu district of Himachal Pradesh.

The time spent in the Park also made him familiar with the cultural heritage of the local inhabitants and their simple way of living that had remained untouched from the influences of the outside world. By the end of his nine-year term, the Park Director had become a complete convert, a passionate park ranger devoting his life to protecting and preserving the Western Himalayas.

It was also the collective effort of Mr Pandey and his many associates that the Park received UNESCO’s world heritage site status in 2014. He believes that the biggest threat to the Himalayas is the environmental destruction being carried out in the name of the development and the solution is ‘roadlessness’, a term which he has coined to explain how roads destroy the ecosystem of an already vulnerable area.

The WildCone recently caught up with him and spoke to him on a range of issues and also about his upcoming book, ‘The Great Himalayan National Park: The Struggle to Save the Western Himalayas’, he has co-authored with Canadian research scientist Anthony Gaston. Here are the excerpts:

Q: You have been closely associated with the GHNP and remained its director for nine years. Has UNESCO’s heritage site tag helped the GHNP in any way?

A: Yes, of course. One benefit is that UNESCO’s heritage status has created an unprecedented awareness about the Park and people know that there is this one patch of wild land that needs to be preserved and protected. The heritage tag has also added an extra layer of protection around the Park in the sense that UNESCO rules and conditions will make it impossible any steps that are harmful to the biodiversity of the Park. UNESCO can always withdraw the heritage status in case it believes conditions of maintaining the Park are not being met.

Q: What are the pressures the GHNP is facing? What exactly is the struggle?

A: The struggle is all about saving the biological diversity of the Western Himalayas. To do this it’s very important that the people are with you. If the GHNP is to be protected then the community there needs to be roped in and get involved. When I was the Park Director, there were these issues about locals grazing their animals or searching for herbs in the Park. We convinced them not to enter the Park by providing them with alternate grazing sites and different sources of employment.

Q: Besides climate change, what is the biggest threat the Western Himalayas are facing?

A: The single biggest threat is the environmental destruction being carried out in the name of the development. This so-called development has started modifying the ecosystems and leaving behind a trail of permanent damage.

Q: What is the solution?

A: It’s Roadlessness –- the absence of roads in vulnerable zones of the Himalayas. If Himalayas are to be saved then build no roads. As soon as you build a road, it creates the ribbon development and is a sure recipe for destroying the biodiversity of that area. Roads are meant for humans. When there were no roads, there was no development and no environmental destruction either. Let nature rule.

Q: There is a greater focus on protecting the GHNP but it seems the other parts of the Kullu district which are equally vulnerable have been largely overlooked?

A: The blind commercialization of the tourism sector in other parts of the district especially in Kullu and Manali has started having an adverse impact on the environment. The need of the hour is practicing Community based Eco-Tourism (CBE) so that the biodiversity could be saved. Why can’t we have ropeways instead of the roads? It’s difficult but needs to be done.

Q: The Uttarakhand High Court had recently banned night stays in the meadows in the forests there. Do you favour similar restriction in Himachal as well?

A: When the Carrying Capacity (the number of individuals an environment can support without significant negative impacts) diminishes, regulation comes in. I think the Forest department should decide how many people can enter the vulnerable forest areas at a given point of time and then implement its own orders.

Q: Mountain treks in Kullu and other parts of the state are facing the problem of littering and plastic pollution. Should the government start imposing penalty on polluters on mountain treks to protect the environment?

A: As I said, the forest department should take charge and decide what to do. They can declare that not more than a certain number of people can go to forests. It’s the responsibility of the forest department. It’s their job and they have failed to check harm to the mountains.

Q: What about the climate change?

A: Talking about climate change, I want to draw attention to some of the exotic species of trees like Eucalyptus and Lantana, which are becoming widespread in some parts of Himachal. There is a myth being propagated that these species of trees are good at Carbon sequestration, the process of capturing atmospheric carbon dioxide, and thus help in reducing climate change. I must say that these trees are the biggest enemies of the environment and should be removed completely.

Q: Yours is one of the few books on the GHNP. What do you want to put across through your book?

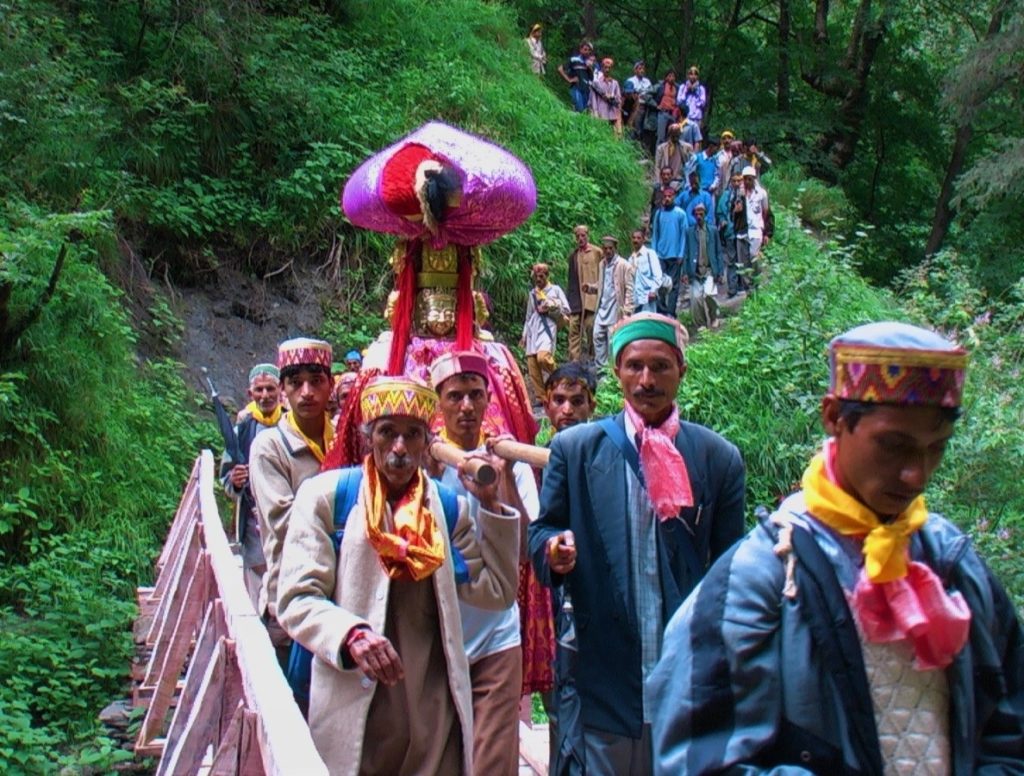

A: This book is not only about the GHNP biodiversity and the Western Himalayas and the need to protect them but also about the cultural heritage, the traditions, and an innocent way of life. Kullu used to have these beautiful Kathi-Kuni architecture style houses. If they were to be in Switzerland, the government there would have preserved them. But here these marvelous houses are fast disappearing and being replaced by concrete structures. We also wanted to draw attention to the sacred deities, trees, rivers, and lakes of Kullu and emphasize on the need to preserve and protect them. It’s a nature-friendly book. The royalty from the sale of this book will go to the cause of protecting and preserving the GHNP.