Profile

THE MUSEUM MAN

Meet Anand Kumar Sethi, who single-handedly converted more than 170-year-old historic Dagshai Jail into a museum, the second such one in the country after Port Blair Cellular Jail…

Anand Kumar Sethi had never felt so upset his entire life as he did on that summer afternoon of 2010. He was standing inside the historic jail in Dagshai and everywhere he looked there were heaps of junk. Whatever the army had discarded over the years was lying inside the jail complex — in the rooms, in the corridors, in the open. Wherever any space could have been found, it seemed, was covered with scrap. The historic jail had been turned into a dumpyard.

“I was shaken to the core,” said Mr Sethi as he recalled the day when he had resolved to clean up the mess and restore this jail’s historic significance.

I had met Mr Sethi for this article on a bright sunny morning in Dagshai. An alumnus of the IIT, Bombay, Mr Sethi, who is in his mid-7Os, lives in Dagshai with his wife. But his association and deep attachment with this beautiful cantonment town goes a long way back.

His father, Bal Krishan Sethi, was the first Indian Cantonment Executive Officer (CEO) of Dagshai from 1942 to 1943 and the entire family stayed in a house right next to the jail. No wonder, Mr Sethi grew up in the cantonment knowing and loving the historic heritage of Dagshai — its churches, old bungalows, cemeteries and the jail.

The jail museum

The jail’s condition had enraged him but restoring a prison that was under army control was not easy.

First, the army needed to be convinced for which Mr Sethi had an idea.

“So, one day I went and met the Brigade Commander and informed him about the condition of the prison and told him how important this place was and that we needed to get rid of the junk and restore the place. I said we could convert this place into a jail museum. I managed to persuade him,” said Mr Sethi as we stepped inside the doors of this more than 170-year-old jail.

The Brigade Commander got in touch with the Military Engineer Services (MES), which had the jail under its control, and in the next few days Mr Sethi had the entire place for himself.

And for next one year, he worked ceaselessly.

The army removed the junk, transferred and kept in nearby Dharampur as Mr Sethi explored every nook and corner of the jail, searching for anything of historic importance, and delved into the history books and research papers to know more about this place.

He made a list of each and every regiment that was deployed in Dagshai and contacted all of them. He arranged for the rare old photographs of various regiments in Dagshai and discovered a more than 150-year-old fire hydrant and a mortar clay grinder inside the jail.

Mr Sethi stumbled upon a black smithy shop as he puts it “by chance.”

“I opened this door to a small room and was surprised to see the furnace and some tools. I realized that prisoner chains and cuffs were made in this room only,” said Mr Sethi while showing me the black smithy shop.

He did a lot of research on the cells where the prisoners were kept and came to know of facts that nobody knew earlier — Like Mahatma Gandhi had spent a night in this prison and his assassin Nathuram Godse was kept here; there was a special ‘T&P’ cell for torturing prisoners and a certain horrible punishment went by the name of ‘Bread and Water.’

He was told about the ‘Bread and Water’ punishment by a British resident.

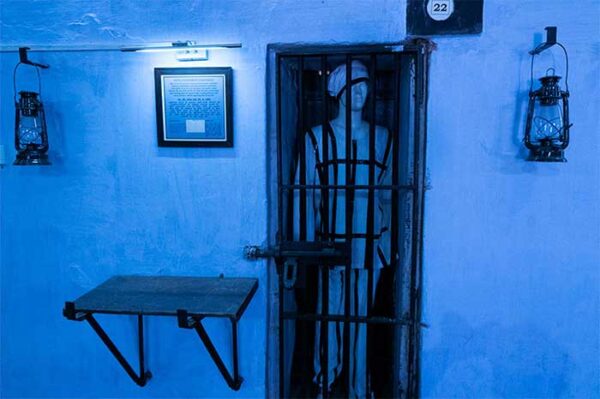

“While the museum work was on, one day I was contacted by a British resident, a Mr Alan Read. He told me that his grandfather was a prisoner in the Dagshai jail and that he underwent what was called ‘Bread and Water’ punishment. It was a form of punishment in which a prisoner was made to stand in the closed gap between his cell door and the outer iron grills and given only bread and water,” said Mr Sethi while showing me through a mannequin how the prisoners were made to stand.

“Alan had some jail papers that he handed over after coming to Dagshai. These papers proved Alan was right,” he added.

Life project

The money used for creating the museum was paid by Mr Sethi and within a year by October, 2011, Dagshai Jail Museum, the second such museum in the country after Cellular Jail Museum, Port Blair, was opened for public.

“I can say that it was one of the happiest days of my life. I was satisfied that I had done my bit to save this place’s wonderful heritage,” said Mr Sethi smiling as we came out of the jail museum.

But it’s not the jail museum alone that he has worked on. He is also behind restoring other historic places in Dagshai like the St Patrick’s church, which was built by the Irish soldiers of Connaught Rangers, the grave of Marry Rebecca Weston, who had died in labour pain with her unborn child, and a mosque in the old bazaar. He has also founded ‘Friends of Dagshai Foundation’ that works on saving the heritage of Dagshai.

However, his life project remains the jail museum.

It’s been a decade since the museum was opened but for Mr Sethi the work on further improving it is still on. “There is so much left to be discovered. New facts keep emerging about this place. The work on the museum will not stop. It will continue,” said Mr Sethi.