Himachal

Trekking

Mahender Lhegdo’s

Everest Ordeal

How is it like to wait for hours in a ‘traffic jam’ in the ‘Death Zone’ on the Everest and then run out of Oxygen?

An Assistant Commandant in the National Security Guard (NSG), Mahender Lhegdo was part of the NSG’s 2019 Mount Everest expedition. He climbed the Everest on May 22, 2019, the day the mountain saw one of the worst traffic jams ever.

The following is an account of his harrowing ordeal on the Everest:

Top of the Mount Everest

Altitude: 8848 meters

May 22, 6.30 am

Standing at the top of the Mount Everest, Mahender Lhegdo knew he was a man in a hurry.

He had just climbed the tallest mountain but didn’t have time for the splendid views from the highest point on Earth or celebration of any kind.

It was quite windy at the top and a shining bright sun had already appeared on the horizon.

Mr Lhegdo gazed around, took off his Oxygen mask, felt the moisture, trapped due to his breathing through the Oxygen mask, instantly freezing over around his mouth, and quickly got some photographs clicked by Furi Sherpa, his guide, for record-keepers as a proof of having climbed the Everest.

The top had slowly started getting crowded and Mr Lhegdo had not been there for more than nine or ten minutes when he decided it was time to go down. He didn’t want to lose another second and get stuck on his way down in what was to become the worst traffic jam on the Everest.

Too many people had chosen to reach the summit on May 22 as the weather gods had finally permitted a weather window, one of the few ones of the season, and he thought sooner he reached the South Summit, safer he would be.

Only less than two hours back, Mr Lhegdo, while ascending, had stood for over an hour at the foot of the Hilary Step, a steep rock and ice wall of around 12 meters and the last bottleneck to the summit, waiting for the traffic of climbers to clear up.

Having started at 7 pm the previous day from Camp 4 at the South Col, he had reached the Hilary Step at around 4.45 am after an excruciating climb of over nine hours. He had not met any queues on the narrow ice ridge from the South Summit onwards but as he got nearer to the summit, he saw dozens of headlamps lighting up the Hilary Step.

It was cold and still.

The only sound he could hear was of his breathing and the harsh wind beating against the rocks and ice of the Hilary Step.

He waited, standing almost still for almost an hour, his body had started to shiver and after some more time he saw a movement in the line ahead of him, heard crampons being dug into the ice, held the fixed line and finally started moving up towards the summit.

These memories of the jam at the Hilary Step were still fresh in his mind as he left the summit with Furi Sherpa and started walking down towards the Hilary Step.

Hilary Step

Altitude: 8790 meters

6.45 am

As he reached and stood over the Hilary Step, waiting for his turn to take the next step, he looked down in dismay — a queue of climbers had formed uptil almost the South Summit. There was no movement; they appeared like ants stuck in a row along the fixed line.

Mr Lhegdo’s worst fears had come true.

He was looking at the worst traffic jam ever on the Everest and there was no way out of it.

The Nepalese government had for this season given permits for climbing Everest to a record 381 people and with their support staff and the hired Sherpas included, there were a maddening 750 people on the Everest. The worst of all, there had been too few weather windows, the ideal weather conditions for the summit push, so maximum people had got bracketed together and aimed for the summit at the same time when that single weather window opened.

They had their best chance to reach the summit and no one wanted to lose it, the strong and the weak, the quick and the slow. And on May 22, there were a record 220 climbers, pushing for the Everest summit, together.

Standing and waiting over the Hilary Step, the time for him seemed frozen like everything else around and every minute that passed was taking longer than usual.

It was for more than 12 hours now that he had been in the ‘death zone,’ the part of a mountain above 8,000 meters where there is little oxygen in the air and where maximum casualities take place, and was well aware of the dangers -– running out of oxygen while waiting in the line, falling prey to the altitude sickness or weather suddenly turning adverse.

The only solace, he thought was the cloudless sunny day. The average day temperature on the summit and near it varies between -20 to -25 degrees Celsius, enough to give you frostbite if body parts remain exposed to this extreme cold for longer duration.

He was shifting his body weight from one leg to another and moving his toes, something which had become absolutely important to keep the blood circulation going in the body.

He had no clues like the rest in front of him or behind when the jam would open or how many people were holding up others. He had been standing in the line for an hour now and during this time he had taken just four to five steps.

He was feeling tired and exhausted but there was no place he could just stand down and sit for a while. He was cramped, standing on the edge with drops of thousands of feet on either side of the Hillary Step. One wrong step and you could go down off a ledge or along with a cornice.

His patience finally started wearing thin. It had been over one-and-half-hour and he had not moved more than five steps. He grew increasingly restless and then decided to ‘overtake’ the slow ones ahead of him, against the advice of Furi Sherpa, who wanted him to stay close to him.

He unclipped one of the two carabiners from the fixed line, waited for the right moment and stepped ahead of the man in front of him down the Hilary Step, clipped the removed carabiner to the fixed line again, then waited, unclipped, overtook another climber, clipped again and so on he went ahead. He thought it was not risky as long as one of the two carabiners remained clipped to the fixed line.

In the days following the deaths on the Everest (11 climbers died including 4 Indians, 9 of them on their way down) many mountaineers had suggested that tragedies could be averted if in traffic jams quick climbers could step ahead of the slow ones instead of waiting in the line.

Tim Mosedale, a British mountaineer who has climbed Everest six times, had told the BBC that “stepping over the rope to rest” could have saved lives on Everest.

“If the person in the front is holding up people and if when they rested and stepped over the rope, people could just Jumar up along, pass them, keep on going. They get rest, other get past and those who are resting won’t hold up people. But they don’t, because they don’t have that awareness, because probably they haven’t been there before,” Tim had told the BBC in an interview.

Back on Everest, Mr Lhegdo was stepping ahead of others cautiously down the Hilary Step. However, this overtaking in the jam was not being really helpful as in the last one hour or so he had managed to walk down a distance of just about 15 to 20 feet.

After almost three hours, he was finally at the foot of the Hilary Step and still there was no end to the long row of climbers emanating from the South Summit.

He waited again and thought it would be too risky to step ahead of others on this narrow knife-edge ice ridge, one little slip and you could end up thousands of feet below.

And then after a wait of over three hours, he noticed a small movement in the line, slowly the steps were being taken, he let out a sigh of relief, the jam was finally clearing up.

But his ordeal was far from over.

Towards the South Summit

Altitude: 8749 meters

9.45 am

As he took steps on the narrow ridge towards the South Summit, he was feeling completely worn out and in need of rest. It was 9.45 am and he had been in the death zone for over 14 hours now, more than four of which he had spent waiting in queues.

As he moved on slowly towards the South summit, he knew he had left behind Furi Sherpa and thought the Sherpa would eventually catch up to him by the South Summit and then maybe they would rest a bit and eat something.

He was around halfway between the Hilary Step and the South Summit when something hit him hard, like a blow of hammer to the head.

A sudden spell of dizziness struck him, he had trouble breathing in, felt all strength waning in his legs and thought he wouldn’t be able to lift them and take the next step.

What’s wrong, why is it happening? First symptoms of altitude sickness? The oxygen bottle?

He checked the Oxygen flow meter. He had run out of the life-saving oxygen.

He froze, panic kicked in.

He turned in the direction of the Hilary Step; Furi Sherpa had the spare oxygen bottle, but was nowhere to be seen. He had left Furi behind by quite a good distance and didn’t know when would the Sherpa reach up to him. He stood there motionless, only thoughts moving at a lightning speed.

What to do? What to do?

He had to do something now. He looked again towards the Hilary Step and still there was no sign of Furi Sherpa. He knew the more time he spent without Oxygen, the more vulnerable he would become to altitude sickness. He needed to do something now instead of just standing and waiting for Furi Sherpa.

Should I borrow Oxygen? But why would or even should anybody help me here?

He saw a woman with her Sherpa guide, who had managed to find a corner on the ridge to rest, and as he hesitatingly approached them, he noticed they had an extra bottle of Oxygen. He removed his mask and asked them for help, requested if they could lend him the spare oxygen bottle till the time his Sherpa guide reached there? Both the Sherpa and the woman looked at him and then looked through him, thoroughly ignoring his presence in front of them.

There didn’t respond, they looked at him as if they were staring into the oblivion, as if they couldn’t grasp a single word of what he had just said.

He withdrew, not feeling really bad.

Why would anybody help me here by endangering their own lives? Who knows if I were in their place, I would have also refused to share my oxygen bottle.

The feeling of dizziness in his head was slowly stepping up and he was thinking of finding a place to sit for a while and wait when he saw a small group of people at a distance but within an audible range. They appeared to be Indians. He shouted out and waved at them but there was no response — no hand was raised, no gesture was made -– from the men in the group busy clicking pictures.

He knew he couldn’t judge anybody here. On Everest, everyman is for himself.

Now all he could do was wait for Furi Sherpa and watch as people passed him by, without even noticing him — a man, standing there and not looking good.

His thoughts whirled back to yesterday to the man, he had seen frozen in ice, his rucksack still on his back and strapped to his shoulders, his harness clipped to the rope, beyond the Yellow Band and near where the route for the Lhotse summit diverges. Utterly shocked, he had felt a chill run down his spine. Nobody knew since how long he had been lying there and no one even cared to know.

He had been standing on one of the most exposed sections of the South Summit ridge with thousands of feet of drop on both the sides and where many often complain of vertigo, for more than 15 minutes without Oxygen and inhaling the thin air and experiencing shortness of breath, besides dizziness and gradual loss of body strength.

All this time, he had not stopped gazing towards the Hillary Step every other second hoping the next one coming towards him would be Furi Sherpa.

And then he saw a man he recognized, coming and waving at him.

He couldn’t help but smile at Furi Sherpa, who had appeared like a guardian angel in the nick of time.

Furi saw his face, understood immediately, changed the Oxygen bottle, and as Mr Lhegdo took a deep breath, he felt as if he was coming back to life again.

The Balcony

Altitude: 8400 meters

10.40 am

His body strength had returned and he was feeling much better now. They walked under a sunny, blue and cloudless sky and soon enough crossed the South Summit. It was not before the Balcony that he finally sat down and rested for the first time after around 15 hours, had some water and ate a chocolate bar.

They descended back to the Camp 4 at the South Col by around 11.45 am and again rested for a while. At the South Col, his other three teammates were already waiting for him. They picked up the clothes and some other small items they had left behind before heading for the summit from the Camp 4 and started further descending towards Camp 2, where they intended to spend the night.

Now, Mr Lhegdo was descending with the expedition team and they were closer to Camp 3 when one of the team members ran out of Oxygen and had a tough time breathing and walking down. Seeing his condition worsen, Mr Lhegdo removed his Oxygen bottle, helped attach his team mate’s Oxygen mask to it after removing the emptied one and told him that if he felt comfortable without the artificial Oxygen then he wouldn’t be needing it anymore.

Mr Lhegdo descended easily without the bottled oxygen and didn’t have any requirement for it any longer.

He was breathing fine.

Epilogue

Mr Lhegado reached the Camp 2 by 8.30 pm and spent the night there. Next day on May 23, they started off at around 8 am and were back in the Base Camp by 1.30 pm.

He had started his Everest climb from the Base Camp on May 19 at 2.30 am and spent the first night in Camp 2. On May 20, he had started at 8.30 am and reached Camp 3 by 2.30 pm. Next day on May 21, he had started at 3 am from Camp 3 and after passing the Yellow Band and Geneva Spur, reached the South Col by 9.30 am. The same day, after rest, he had started for the summit at 7 pm in the evening.

Mr Lhegdo had landed in Nepal on April 1 and reached the Everest base camp on April 14.

(The Everest 2019 was one of the deadliest seasons ever in which 11 people including 4 Indians lost their lives, mostly due to exhaustion, high altitude sickness and accidental falls.)

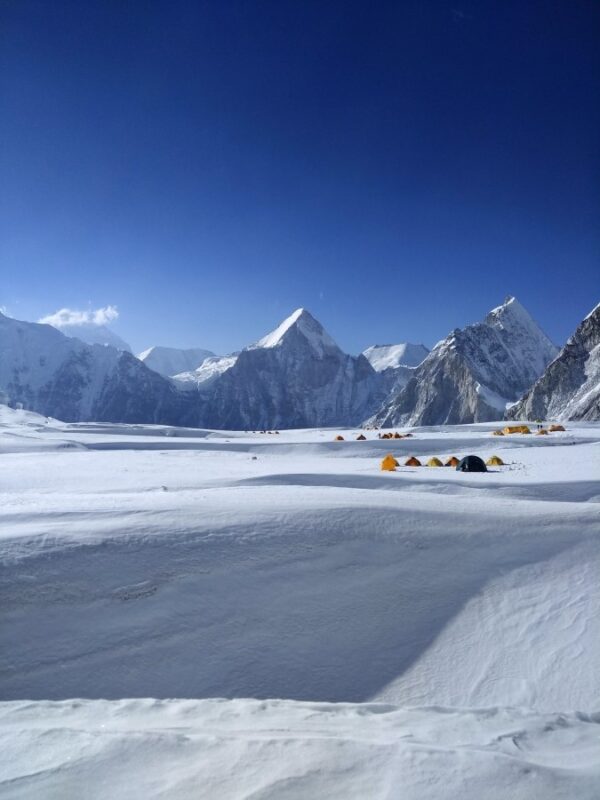

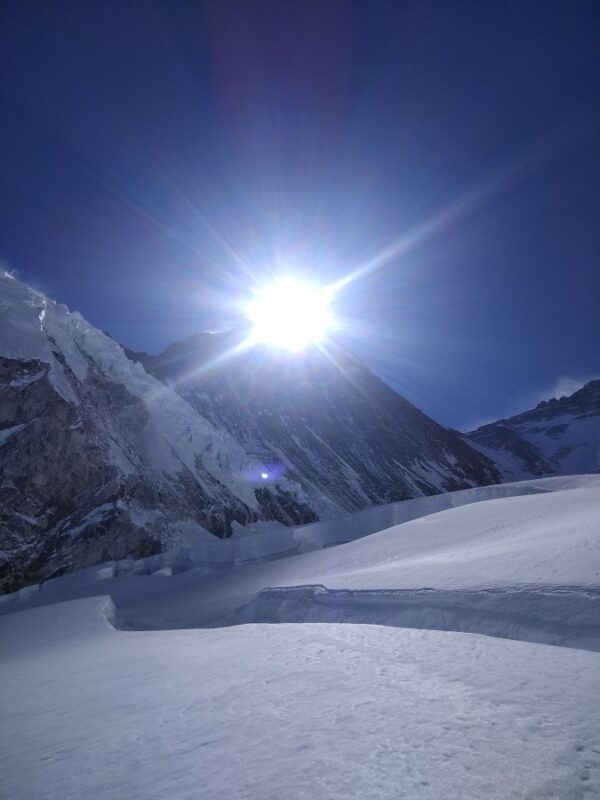

Pictures

Here are some pictures, mostly clicked by Mahender Lhegdo, during his trek to the Everest Base Camp and while going up the Everest:

Great Story…..

Proud of you bro….

Thank you Wildcone for your attention…

Wah g wah. Jisne b likha hai shandaar likha hai.

Awe inspiring

B’tfully jotted

Congratulations to #Everester…..???